What an amazing day in history!

The U.S. Supreme Court has upheld a piece of legislation that the Brackeens, a white couple from Texas who felt ‘called’ to adopt American Indian children, fought to overturn. The Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 (ICWA).

They weren’t the only foster parents who have fallen prey to becoming pawns in the anti-ICWA lawsuit crowd. They were just the most recent.

ICWA was the legal response to the Indian Adoption Project, a social experiment that sought to measure if American Indian children removed from their Indian families and tribes would thrive when placed into non-Native homes. The study was conducted between 1958-1969, in an informal agreement between the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Child Welfare League of America. The CWLA has since apologized for its role in the study.

Early findings of the Indian Adoption Project indicated that children did indeed seem to thrive. Nearly 400 children were in the pool of the project. The project received over 5,000 adoption applications from white parents who sought to ‘save the poor, forgotten Indian child.’ At that point, the flood gates opened for anyone interested in obtaining or placing an American Indian child. Placements were handled by state social services, private agencies, as well as religious agencies, including Catholic Charities, Lutheran Family Services, the Pentecostals, The Mormons, and the Jews. By 1972 it was estimated that between 25% and 35% of American Indian children had been placed into non-Native homes. A third of the American Indian child population!

It should be noted that David Fanshel, the lead researcher, did provide a caveat to the findings. “My study has followed the children while they are still relatively young and just about to embark upon their school careers…It is to be expected that as our Indian adoptees get older, the prevalence of problems will increase… (Fanshel 1972, 323). Because, Fanshel states, that during adolescence the factor of racial difference looms larger (Fanshel 1972, 339). But his biggest contribution to what would become ICWA was his belief that the United States shouldn’t determine what should happen to Indian children; that should be left to the tribes. “It is my belief that only the Indian people have the right to determine whether their children can be placed in white homes (Fanshel 1972, 341).”

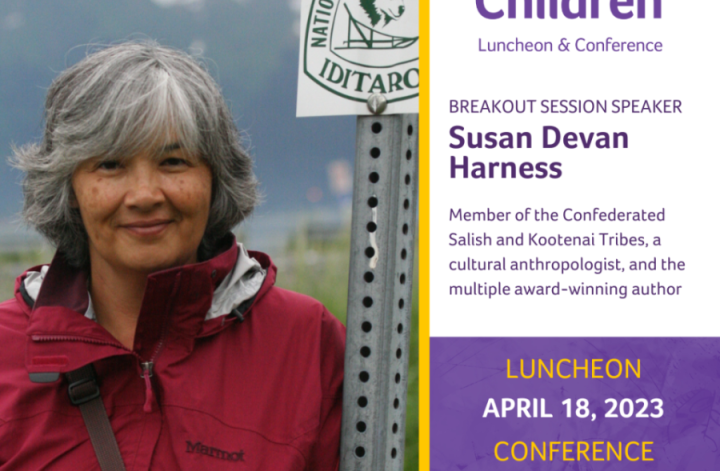

ICWA was established to protect American Indian families, communities, and tribes from the genocidal practice of interracial child adoption. By 1978 their children were flying off the reservation as biased, well-meaning but misguided non-Natives sought, and continue to seek, a home in which to provide a safe haven for the ‘poor, forgotten Indian child.’ Except bringing an Indian child into the dominant culture that has a long history of anti-Indian sentiment, didn’t provide a haven. In fact, that practice is extremely harmful to the child (Harness, 2018). The wounds inflicted by the dominant culture in their racist slurs, long-held attitudes, and beliefs of low academic abilities and achievements, perceived genetic characteristics that make us prone to substance use and abuse, as well as a general perspectives that American Indians are lazy and government subsidized do so much harm (Harness, 2009). We carry so much shame on our small shoulders and have for too many decades, thanks to such acts of saviorism.

The dominant culture, which has fanned long-held beliefs about American Indians, is ruled by old white, moneyed men. This same group is the one that filter insidious information to others in the group about who makes better parents, without telling the whole story of forced assimilation, of the 1,000 wars fought against American Indians on our soil since 1775, of Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830, of Indian education, which I call cultural re-education, that was implemented through religious schooling and given finesse by the U.S. government boarding school programs. Don’t forget the Termination and Relocation Acts of 1950s, or of American Indian interracial adoption of the 1960 through the late 1970s. Every single one of these pogroms on U.S. soil was designed to annihilate the Indian. If they couldn’t kill us, they’d make us become one of them. That way, my thinking goes, when they screw us over, we won’t notice because we’ll all be on the same page. This ruling class of old, white, moneyed men stand to benefit the most of our disappearance, in terms of land and acquisition of resources, which is really what the Indian wars and culture wars have always been about.

The bloody battles with tribes still continue, moving from the grasslands to the courtrooms.

And if you think I’m being dramatic, I want you to consider this one question:

How would you feel if your white children were physically taken from your family, your community and placed with an American Indian family in and American Indian community because it was considered, by the law in the land, to be in the best interests of the child?

Fanshel, David. 1972. Far from the Reservation. Scarecrow Press.