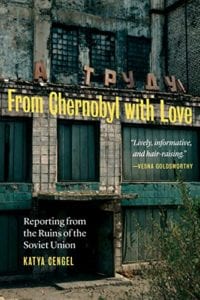

Katya Cengel, author of From Chernobyl with Love, looks younger than her forty-something years. Maybe it’s her smile, maybe it’s her thoughtful blue eyes, maybe it’s the look of a dreamer that she gets when I ask her questions about her reactions to living in Eastern Europe. Or maybe it’s not about youth, but about her embracement of life. Her excitement, even through the airwaves is palpable, so how could I not be drawn into the wonderful, insightful conversation we had about her work as an author? What I came away with is she’s as much fun to talk with as her book is to read.

Katya Cengel, author of From Chernobyl with Love, looks younger than her forty-something years. Maybe it’s her smile, maybe it’s her thoughtful blue eyes, maybe it’s the look of a dreamer that she gets when I ask her questions about her reactions to living in Eastern Europe. Or maybe it’s not about youth, but about her embracement of life. Her excitement, even through the airwaves is palpable, so how could I not be drawn into the wonderful, insightful conversation we had about her work as an author? What I came away with is she’s as much fun to talk with as her book is to read.

In 1986 I was in my late-twenties when the Chernobyl disaster happened. News of the nuclear meltdown ricocheted around the globe, revealing the problems of a Ukraine, really, all of Eastern Europe, that resided in a post-Soviet Era. I knew little of this region, other than what I gleaned from the news: a country and culture of extreme instability, and a land that was home to extreme difficulty and hardship. Who would want to go to such a place? Katya, this adventurous, twenty-something, recent journalism grad jumped at the chance.

“It was the flyer,” she answers to my question of ‘why’, with her trade-marked broad smile. It read, If you like the idea of covering infant democracy and whirlwind business but cringe at the idea of living in a Brezhnev-era apartment building, don’t apply. As soon as her application was accepted, she booked her flight.

I ask her how much research she’d done about Latvia, the first country she worked in, before landing? She laughs. “Not much.” Katya did do some basic internet research, which required a lot of patience because most of the sites were under construction, which meant they didn’t yield any information at all, and slow transference speed meant it took ten minutes for a page to load, and you had to hope it had the information you were looking for. Aside from that she had a basic guidebook, a couple of other books about the country, as well as a copy of the Economist. “It wasn’t much.”

I ask if she was worried about the reality of being in this foreign space. Katya thinks for a moment, smiles, and cocks her head a bit and shrugs. “Somewhat.” However, in her book, Katya admits that the descriptions of the Baltics were a bit intimidating. “A restless and, in some cases, rootless Russian population, leaders who tended toward nationalism, and a business model that seemed to include mafia involvement…” Again, I find myself asking a silent question of ‘why.’

Evidently others did too. As Katya stood at an airport in Europe waiting for her connecting flight, she was approached by a group of young missionaries, interested in her travel choice. She was, after all, standing at the gate which announced where she was going.

I ask her if what they said worried her. Her eyes sparkle with just a hint of mischief. “I would have been more worried had I known what a departure from protocol it was for missionaries to be quizzing me on my language skills instead of my belief system! They asked things like ‘Did I know Latvian? Did I know anyone in the country? Had I ever seen a hard copy of the Baltic Times? Did I know if the company had money to pay me? Did I have a phone number for Steve or an address for the newspaper? Did I know if anyone would meet me at the airport?’ My answer to pretty much all of their questions was the same: no. Except for the last one. Steve knew my flight details…at that point the missionaries seemed concerned.”

Gentle reader, don’t worry. Steve, the publisher, met her at the airport and they recognized one another as the only two smiling Americans amidst the “crowd of dour Latvians.” “It was as if no one had told the people in the waiting area that the Soviet Union had collapsed, and they were no longer prisoners of their government,” she writes with wry wit.

I ask where what was unfamiliar about this space. “People don’t smile,” she answers quickly. “Everyone looks miserable all the time. And the cold! I wasn’t prepared for the cold.” She wasn’t used to the fact that it would start snowing before Halloween and stop in late spring. “I didn’t realize that people had two entirely different pairs of shoes, one for inside and boots for the outside. That just seemed like so much work to pack different shoes to and from your workplace.” Coming from just north of L.A., that was understandable.

But there were other differences as well: people were paid in cash; the country had a lot of holidays and Name Days—a practice of the early Christian church to commemorate saints and angels, and then to commemorate people who were named after the saints and angels, and finally to just commemorate everyone. The Latvian locals were nice as they helped her navigate her new home. Not so much the Ukrainians, among whom she lived when she returned to the Baltics several years later. The Ukrainians were more stand-offish with their own lives. She also was surprised at the sometimes-overwhelming loneliness. “I am used to being alone, and I like it. Sometimes it would just hit me how far away I was and how I didn’t have a social network like I had in Latvia. I was a foreigner and sometimes I felt so out of place.”

I ask her what she learned about herself from taking on this adventure. She speaks again about the loneliness, “You can have too much of it I realized.” She talks about the perks of being a foreigner, treatment that became addictive to some people. “When you’re a foreigner, you’re given special status, you receive special treatment. I had to remind myself that I didn’t want to get too comfortable with that specialness. It’s easy to get comfortable with it.”

Although there were challenges to international travel, Katya admits that she feels she’s met those challenges: living on her own and navigating new cultures, learning languages and the social politics, all of which have made her confident in her independence. “I like thinking I’m tough,” she says, again with a quick smile. Not only tough, but adaptable. She didn’t have access to peanut butter or coke, but she learned the different ways she could obtain these treasured pieces of American culture. “I feel that if something is challenging, the rewards for getting through it are greater. The most mundane things take on a sense of specialness.”

As I reflect on her words, I think the idea of challenges, of true challenges, for most of America, have been lost; we can obtain anything we want, any time we want, and we whine when those distribution networks get interrupted. Just think back to March, 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic hit and its effects on commerce began to affect everyone. Grocery shelves were nearly empty and toilet paper became almost a commerce of its own. This lack of access was on the news every single night, with new images, new video. It was something that the average person in America had never had to face, and we didn’t do a good job of meeting those challenges quietly.

It is at that moment that I realize we were required to rely on people instead of institutions to get what we needed. Which is exactly what Katya says she learned in the Ukraine. “You learn to trust the people and distrust the government – it can’t take care of you. Here in the U.S., you put your money in a bank; there you would never consider such a thing. However, if you put money inside a book, and gave that book to a person on a train, to give to your mother in another part of the city, it would get there.”

I grow quiet in imagining this in a country where water is not necessarily clean nor drinkable, where electrical power is tenuous because of constant disruptions, where a trip a few hundred miles away will take twenty-four hours, by train.

“How is that”, I ask.

Katya smiles, and her blue eyes get that far away look as she says, “Simplicity.”

That’s when you begin to understand how little you really need to survive.

6 Comments

I love this! Thank you for an inspiring interview.

Thank you, Teresa. I love getting to know someone through their words. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Enjoyed the interview. What an adventurous woman. Love that! Too many people are fearful of taking risks. When I had a stop in AbuDabi United Amirtes a few years ago, I felt like just checking out the place but I was enroute to India and was expected. Traveling around Europe for a couple weeks many years ago gave me lots of freedom and adventure w my eurail pass. Amazing who you meet on your own. I always kept a journal so it is fun to go back and relive the adventures.

Angela, so good to hear from you! I’m not overly adventurous, so living these experiences through someone else is really a fun exercise! And being open to talking to strangers while traveling gives you a window into a culture. Thanks for your note!

Just finished your Book Bitteroot, tears were never far as I was also the same victim of this terrible system and am in honour to your honesty. I have tried for years to explain why I felt the way I did, to no avail and was always told ” how grateful I should be” Your words too were such a comfort to my batterted mind, thinking I was the only Native child to have these feelings. Thank-you from the bottom of my heart for puttting MY feelings on paper. I am from Canada, and I continue to research, What the heck happened and why? My heart will never settle. Again Thank-you. I am indebted to you. Native child from the proud people of the Tl’aztten nation of Lake Stuart, in B.C. Canada. Brenda

Brenda, thank you so much for writing. The book was written for us – American Indian children raised in white families, to come together and understand the world we found ourselves in – a traumatic world that adoptive parents many times have no idea exists. Thank you again.