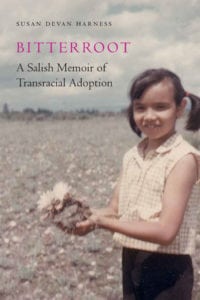

Bitterroot: A Salish Memoir of Transracial Adoption. University of Nebraska Press, Oct. 2018

Bitterroot: A Salish Memoir of Transracial Adoption. University of Nebraska Press, Oct. 2018

My brother, by blood, materialized from a bend in the hallway as if by magic, a genie from the lamp. “Hey, I heard you were looking for me.” He smiled beneath his mustache. We didn’t hug; it seemed too intimate for a person I’d seen only three other times in my life, times of uncertainty and stress, times when it would be relatively easy for him to forget that I’d ever existed. I’d been removed from my reservation family at the age of eighteen months and adopted by a white couple when I was two. He wasn’t born until I was ten and living a very different life with a very different family.

As we stood in the hall and talked the mundane, safe talk of people who are essentially strangers, I studied him, looking for the familiar. Although he was not much taller than my five foot six stature, his frame was large and intimidating. His skin was lighter than mine, something that confused me; I figured since we shared the same mother, we’d also share the same color skin. Both of us had black hair, except mine was streaked with paths of silver, and his was cut close to his scalp and stood straight up. I listened to his voice, the way he spoke. I watched his gestures, and saw only one other characteristic that was familiar: each of us had brown eyes, but his didn’t blink as they studied my face.

At one point he leaned his back against the wall and hooked his thumbs in the pants pockets of his police blues, crossing one foot in front of the other.

After a few moments of silence and that unwavering gaze, he said, “I used to dream of you.”

At once, I was both intrigued and confused.

“How old were you,” I asked, “And what did I look like?” I didn’t understand how he could dream of someone he’d never met, or what role I could have possibly have played in his life.

“About eight. You looked like my sister, Robin.”

“What did you dream?”

He watched me for several moments before replying. “I used to dream that you would come back from wherever you were and take me away from all of this.” He paused, his gaze still on me. “I used to dream that a lot.”

My heart shattered, like ice on granite. It shattered for both of us. Because what my brother didn’t know, couldn’t possibly know, was that I’d dreamed of this family as well. I dreamed that they hadn’t forgotten me.

I imagine he wondered about the life I might have given him, just as I wondered about the life I sought, a life where I was “real” instead of “adopted”; a life where my skin color was the same as everyone else’s and I wouldn’t stand out, isolated; a life where “American Indian” meant something more than “I don’t know.”

So as we stood in that hallway and regarded one another, deep in our own dreams, each of us were looking to be rescued by the other.